Under the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, a number of museums serving as public spaces have been temporarily closed in consequence of the government-imposed lockdowns and precautionary measures, thereby being unable to present the meticulously curated exhibitions and artworks. Many of them decided to utilize different kinds of digital media means, such as the 360-degree virtual exhibition created using real-scene shooting, live-streaming guided tours, etc. By converting the venue from physical space to cyberspace, museums attempt to continuously promote the exhibitions and relevant researches —— as the outreach to audiences that are unable to visit their sites in person. Take the “ZKM | Center for Art and Media Karlsruhe” (hereinafter referred to as ZKM) as an example. In the face of this challenging circumstance, they had organized a virtual exhibition of crypto art that predominantly featured generative digital artworks, thus arousing heated discussion in recent times.

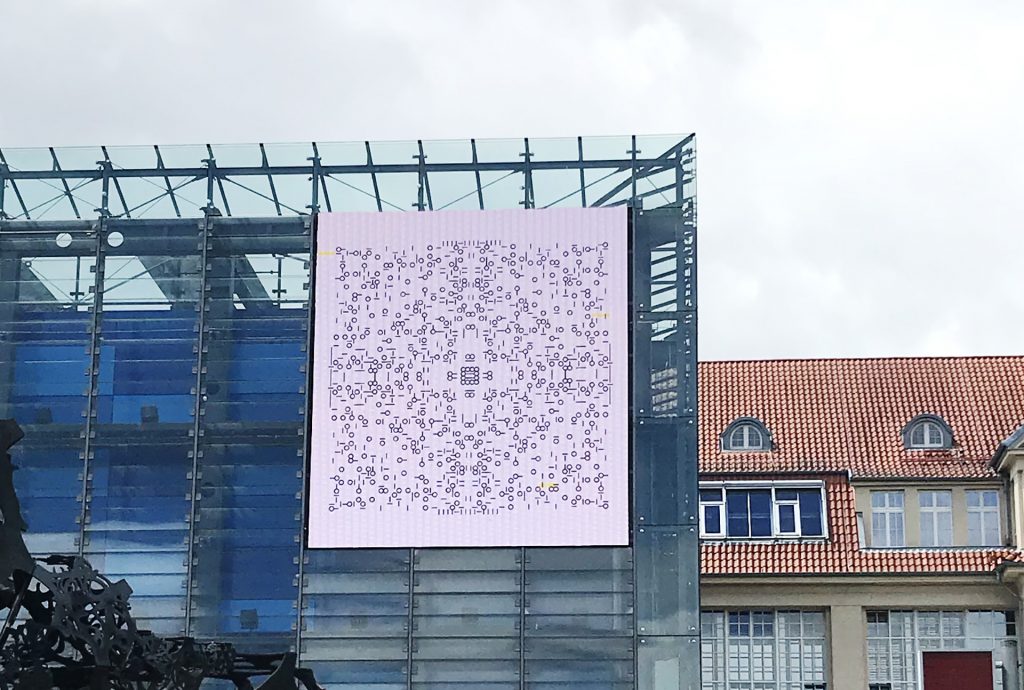

Despite being considered a virtual exhibition, “Crypto Art – It’s Not About Money” still combined online content pertaining to crypto-art-related knowledge and an offline visual representation that took place in its venue: the former took the form of a website, which traced the development of blockchain, NFTs and digital art based on the research performed. Also, in partnership with the “Art Blocks”, a platform dedicated to generative NFT (Non-Fungible Token) [footnote 1] artworks, the hyperlinks to the transaction process pages were directly posted on the said website; the latter was on view through a large LED display screen on the ZKM cube, a building with glass façades located in the square in front of the museum. It featured a selection of works from both the ZKM’s NFT collection acquired in 2018 and private collections, all of which were showcased in a way that resembles window displays with the aim of reaching a wide variety of audiences during the lockdown period.

According to the history of NFTs, the first experimental NFT artwork —— that is to say the piece by artist Kevin McCoy, can be dated back to 2014. He was truly fascinated by how blockchain technology has allowed artists to sell their art directly to their fans without a broker [footnote 2]. Following that, in May 2014, McCoy, together with his tech partner, Anil Dash, launched the project “Monegragh” at the Rhizome’s annual conference “Seven on Seven” at the New Museum, New York. Furthermore, McCoy sold a GIF that was created by his partner to Dash onstage and then demonstrated the transfer of ownership of that GIF using the Namecoin blockchain [footnote 3], which laid the foundation for “Monegragh”, a platform utilizing blockchain technology to authenticate digital objects. In the same year, another blockchain-based registry for digital art called “ascribe” was founded in Berlin. Shortly after, in 2015, an artist that has long focused on the development of blockchain technology, Harm van den Dorpel (he had already created a blockchain-based artwork that was sold to the Museum of Applied Arts in Vienna with Bitcoin way before all sorts of NFT trading platforms emerged. [footnote 4]), started “left gallery”, which offered downloadable digital artworks with blockchain authentication for trading.

The NFT marketplace platform, “left gallery”. Screenshot via: https://left.gallery.

At the end of 2016, two software developers John Watkinson and Matt Hall co-created by far one of the most renowned NFTs: CryptoPunks. They launched a pixel character generator designed to create all possible combinations of randomly selected visual characteristics (such as the types of sunglasses, skin tones, hairstyles, and so on); the total outcomes are 10,000 24×24 pixel avatars that are collectible and tradable in a similar way to valuable baseball cards. With the specific technical method developed by them, these generative characters’ individual traits and chain of title can be tracked on the Ethereum [footnote 5] blockchain, which enables CryptoPunks to hit the market since June 2017. However, only five months later, this kind of on-chain transaction became obsolete after CryptoKitties, developed by artist Guile Gaspar and his team, Dapper Labs, went viral. These algorithm-generated digital cats are not only as collectible as the CryptoPunks avatars but also breedable, that is, CryptoKitties is a blockchain game allowing players or so-called collectors to breed virtual cats by matching pairs so as to unlock rare “cattributes” and increase the value of their furry friends. In fact, it was so popular that the Ethereum network once crashed owing to high transaction volumes.

CryptoPunks (2016), created by artists John Watkinson and Matt Hall. Photo courtesy of LIN Tzu-Chuan.

CryptoKitties (2017), developed by artist Guile Gaspar and his team, Dapper Labs. Photo courtesy of LIN Tzu-Chuan.

In response to the craze for virtual cats, in October 2017, the ZKM held the exhibition “Open Code. Living in Digital Worlds”, in which they began to explore the topic of blockchain. As the in-house technician and software developer, artist Daniel Heiss conceived a project named “Krypto-Lab” as part of the exhibition with a view to explaining blockchain technology in a way that is comprehensible to the general public through workshops, lectures, and exhibits. In the course of this project, the ZKM acquired CryptoPunks, CryptoKitties and the work event.listeners by Harm van den Dorpel. Judging from the fact the ZKM, as an art and media center, takes concrete action to purchase these significant digital art pieces within a certain era to build its collections, to some extent, their aim is to keep track of the development of NFTs. These artworks have therefore become the archival materials available for future review.

Coming back to the topic of NFT trading, in general, the buyers of NFT artworks will receive a certificate of ownership in the form of a digital token, which points to the file that is either directly stored on a blockchain or uploaded to a web server or to the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) [footnote 6]. However, ever since the ZKM started buying generative art of this kind, they centered specifically on the NFT artwork that is stored and generated on-chain —— the code that generates the artwork, to be exact. In this context, the ZKM is able to find a common solution to the purchase and storage of NFT artworks, as well as further explore another dimension to blockchain.

Autoglyphs (2019), an on-chain algorithmic art piece created by artists John Watkinson and Matt Hall. Photo courtesy of LIN Tzu-Chuan.

Technically, all the relevant information about the on-chain NFT artworks, including the algorithm used for generating NFTs, is stored on the Ethereum blockchain where data is immutable and openly accessible to the public. In a way, the artworks are undoubtedly secured on the blockchain as long as the Ethereum blockchain remain in existence. Autoglyphs was one of the on-chain algorithmic art piece created in 2019 by the artists who fathered CryptoPunks as mentioned above, John Watkinson and Matt Hall. This work is currently on display in the collection exhibition “Writing the History of the Future” hosted by the ZKM in 2019, together with other masterpieces by A. Michael Noll and Kenneth C. Knowlton, both of whom are regarded as the pioneers of digital art.

In spite of the promising future of crypto art, artist Memo Atken expressed his own perspective through an article, “The Unreasonable Ecological Cost of #CryptoArt” [footnote 7], published at the end of 2020. He wished to raise public awareness of the high energy consumption of blockchain technology, which fuelled the controversy over the fundamental yet critical consensus mechanism of blockchain: Proof-of-Work (PoW) —— it requires high-performance computing to achieve the goal of adding new blocks to the blockchain through a time-consuming process; meanwhile, the computer’s operating system needs to remain in high-performance power mode. PoW is initially designed to prevent hackers from gaining unauthorized access to systems, initiating malicious cyber-attacks, and getting the corresponding rewards. However, as suggested by the statistics in the Digiconomist’s analysis, like in many other researches, the annual power consumption of the Bitcoin network was estimated to be 124 Megawatt-hours (MWh), which equals to Pakistan’s total final energy consumption per year. [footnote 8]

Obviously, this has been considered the major disadvantage of blockchain technology; hence, developers from all over the world made their best endeavours to develop new consensus mechanisms based on other technologies, such as “Proof of Stake (PoS)”, in hope of reducing energy consumption and minimizing the threat to our climate. Being actively engaged in the discussion on ecological issues in recent years [footnote 9], the ZKM has taken the decision to suspend the purchase of the NFT artworks stored on Ethereum in response to the said controversy, thus paying close attention to the development of alternatives to blockchain. As the debate over the blockchain’s energy consumption reaches its peak, artist Harm van den Dorpel published an article entitled “Tokenizing Sustainability” in February 2021[footnote 10], which summarized his personal experiences of creating on-chain artworks and running the “left gallery” as a digital art-trading platform since 2015. As stated in the article, he supported the idea of replacing PoW with PoS, for the latter comes with a number of improvements in terms of the environmental impact of NFTs. Yet, he also pointed out that, in addition to the blockchain-induced environmental concerns, we should question how environmentally destructive the Google Data Centers or any other network services that we use on an everyday basis would be. What is reason behind the much less attention paid to the electricity consumption of these daily online activities in comparison with the energy-intensive blockchain network? All in all, these particular issues beneath the surface of technology, which seem closely linked to their conflicts with trading business or social activities, are things worth thinking about.

- Footnote 1: NFT is the acronym for “Non-Fungible Token”, which is nether interchangeable nor divisible. Each NFT is represented by an exclusive identification code. In line with the immutability of blockchain, NFTs are one-of-a-kind items that can’t be replaced with something else. The resulting “immutable authenticated digital signatures” can be used as proof of the source and transaction record of digital artworks, thereby protecting NFTs from being replicated.

For further information, see https://www.rayskyinvest.com/29482/what-is-nft - Footnote 2: In May 2021, The New York Times’s special report on NFTs, “The Untold Story of the NFT Boom”, sorted out the timeline and developmental context of NFTs as the foundation for discussions about the reasons behind the current NFT craze.

For the full-text article, see: https://www.nytimes.com/2021/05/12/magazine/nft-art-crypto.html - Footnote 3: Starting from this year, the Rhizome has published numerous articles on issues associated with NFTs, one of which entitled “Another New World” began with the 2014’s “Seven on Seven” conference where artists Kevin McCoy and Anil Dash launched their project. For the full-text article, see: https://rhizome.org/editorial/2021/mar/03/another-new-world/

- Footnote 4: In 2015, Jack Smith IV published an article “Viennese Art Museum Uses Bitcoin to Buy a Screensaver” at the Observer.com, briefly sharing his views on the Viennese Art Museum’s purchase of Harm van den Dorpel’s work with Bitcoins —— that is to say the “first” museum in the world to have acquired an on-chain artwork with cryptocurrency. For the full-text article, see: https://observer.com/2015/04/viennese-art-museum-uses-bitcoin-to-buy-a-screensaver/

- Footnote 5: Ethereum is an open-source, public blockchain platform featuring smart contract functionality. With the native cryptocurrency, “Ether (ETH)”, the Ethereum Virtual Machine (EVM) works like a decentralized computer so as to run smart contract deployment. For more information, see Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethereum

- Footnote 6:With the mission to provide a better file transfer performance than HTTP, the InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) is a communication protocol designed to store and share data through a distributed file system to ensure long-term data retention. For further information, see the official website of the IPFS: https://ipfs.io/#why.

- Footnote 7: For the full text of the article “The Unreasonable Ecological Cost of #CryptoArt” written by Memo Atken, see https://memoakten.medium.com/the-unreasonable-ecological-cost-of-cryptoart-2221d3eb2053

- Footnote 8: A detailed statistical analysis of the Bitcoin energy consumption has been published on Digiconomist, see: https://digiconomist.net/bitcoin-energy-consumption

- Footnote 9: In May 2020, the ZKM held the exhibition “Critical Zones” that focused on themes surrounding ecosystems on earth, environmental and climate issues. For further information, see: https://zkm.de/en/exhibition/2020/05/critical-zones

- Footnote 10: For the full text of the article “Tokenizing Sustainability” written by artist Harm van den Dorpel, see his personal website: https://harm.work/news/tokenizing-sustainability

- Official website of the exhibition “CryptoArt – It’s Not About Money”: https://zkm.de/en/exhibition/2021/04/cryptoart